A friend of mine went to a Test & Tune event recently and used the opportunity to experiment with his shock absorber settings. He’d been running them full stiff in competition. He decided to start the day full soft and work his way stiffer.

At full soft the car became very loose with dramatic oversteer on corner entry. The oversteer/understeer balance gradually changed as he stiffened the shocks. He was working all four corners together, simultaneously making the “same” change to each shock.

He asked me this question: “How does [adjusting] damping change a car balance like this?”

Here’s my answer.

A basic tenet in structural design is that when a load travels through two (or more) paths, the load preferentially and proportionally follows the stiffer path(s). So, changes in stiffness alter the proportioning of load, say transient cornering loads, from one corner or one end of the car to the other corner or end. Since shocks only create forces that oppose motion, roughly in proportion to how fast the shaft is moving, they become variable, non-linear stiffness elements in the load paths, parallel with and additive (bump) and subtractive (rebound) to the steel spring stiffness. The forces they produce are the dominant effects that shocks have on car handling balance, not energy absorption, i.e. not “damping,” but we will talk about both.

The cornering load can preferentially go to one end of the car or the other. If it can’t be resisted by the tire patch at that corner, then that corner starts to slide.

However, shocks act mostly only during transients when the shock shafts are moving, say during corner turn-in. Steady-state cornering balance is not significantly affected by shock settings because at that time the shocks have stopped moving and are not producing any force.

Now, this last is not strictly true in reality. The shock shafts are always moving to some extent because no surface is completely flat and smooth, plus the damned driver keeps turning the steering wheel, even if only in small, short motions! This is part of why shock valving has a significant effect on the total grip even on relatively smooth surfaces. During steady-state cornering when the shocks are not moving the understeer/oversteer balance at the limit is mostly determined by front-to-rear tire grip differences, weight distribution, spring stiffnesses and anti-sway bar stiffnesses.

That said, the first key point I want to make is that the front and rear shocks are usually not valved the same and generally not acting through the same geometry and motion ratios. So, even though you may think you are changing all four the same amount, say 2 clicks each, it’s not actually the case that the damping change is equal at each shock or wheel. The oversteer/understeer balance at the limit is almost certainly being altered even though you think you’re making equal changes at each shock. Of course, if you change just one end, the effects on car balance are increased.

My second key point is that while shocks do absorb energy, perhaps more importantly they affect the timing of energy delivery to the tire contact patch. Let’s talk about energy absorption first and timing second.

When a car turns into a corner there’s a finite amount of momentum created by the turning action. The shocks on both sides of a turning car absorb some of the kinetic energy associated with that momentum by doing work (force x distance, converting kinetic energy into heat) and they also alter the distribution of load around the four corners by being stiff elements in the load path. Most of the kinetic energy is not absorbed by the shocks and ultimately becomes either temporarily stored in the outside springs (and it’s going to come back out!) or transferred as load to the tire contact patches. If you soften the shocks less energy is absorbed leaving more to hit the tire patch, since the amount of energy stored in fully compressed or fully extended springs is always the same. Soft shocks will allow a faster peak roll motion, in terms of degrees of roll per second, which can affect what happens at the tire patch later when the roll motion is finally snubbed at the end of the roll. All rolls must end.

When the shocks are set stiff they generally absorb more energy early in the roll (both the compressing and the extending shocks) and slow the roll by opposing it with force. This actually transfers load, lateral load (not weight!) to the tire patches sooner in the cycle, thus improving transient response by speeding up the transfer of lateral load to both tire patches, left and right. Theoretically this can act to reduce load shock to the tire patches at the end of the roll and thus help prevent the tires from losing grip. There is literally nothing worse than a car that’s so soft and has so much suspension travel that everything seems fine on turn in until the roll gets snubbed at the end and suddenly all hell breaks loose.

On the other hand, shocks stiff in rebound but not compression act to resist roll only by pulling vertical load off the inside tire patch as the car begins to roll and the shock extends. This can also cause the car to lose grip very early in the turn if inside tire grip is the limiting grip variable. So, if you have a Koni Yellow, for instance, which is adjustable in rebound only, and you crank it up to full stiff, you do not increase the compression damping on the outside tires during turn-in. You only increase the rebound damping on the inside tire, the one with the shock that is extending. The weight pulled off the inside tire still becomes load on the outside tire. (Where else could it go?) My point is that the effects of rebound and compression damping are complicated and not identical opposites.

If stiffer shocks create forces that oppose roll while speeding up lateral load transfer, that necessarily means that lateral load transfer occurs early while the car is at a lower state of roll than otherwise and therefore the tires have not yet given up all the camber they will when full body roll is achieved.

Maybe you should read that last sentence again. I just wrote it and I’m going to read it again! I’ve never seen that fact in print before. Anywhere. It basically defines a mechanism for an increase in grip during the turn-in transient that is due to the shocks changing the timing of lateral load transfer with respect to “weight” transfer, not the amount of lateral load transfer and certainly not the amount of “weight” transfer.

And all this happens in about a second in a slalom.

Maybe we need a diagram.

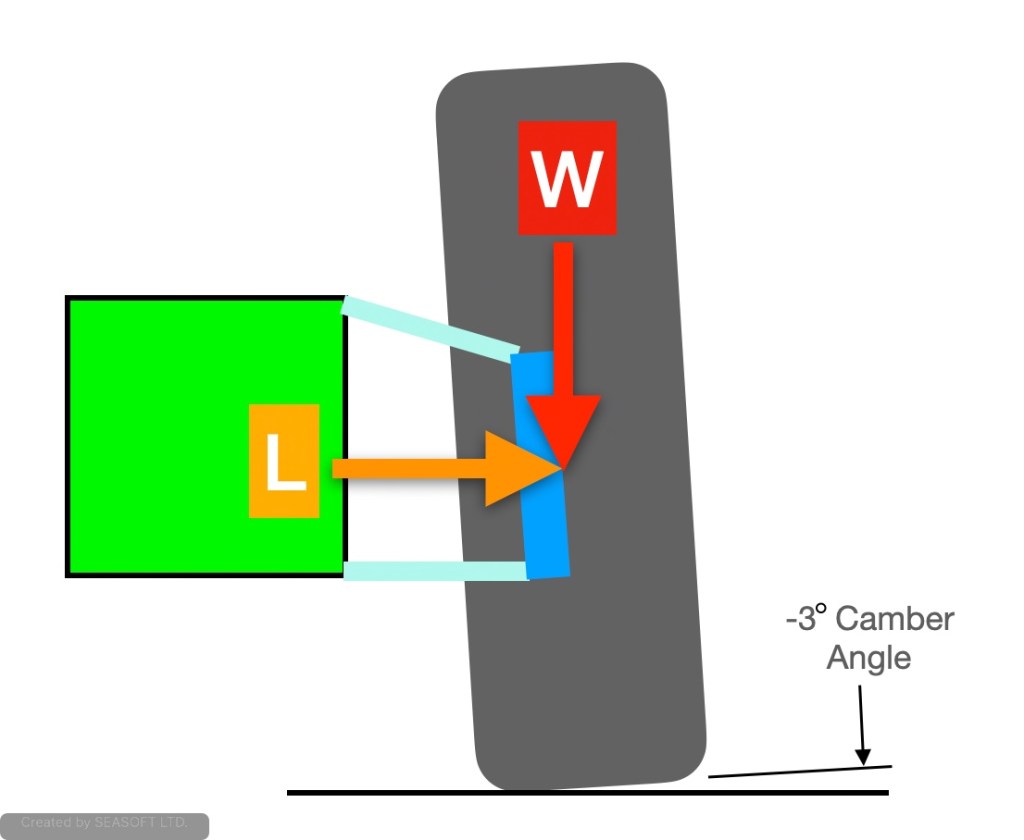

In the diagram we have two forces shown acting on the tire: W stands for weight and L stands for lateral load. Just for fun and so you can develop an eye for it, the wheel in the diagram is actually tilted at 3.6 degrees of negative camber. (I meant it to be 3 degrees, but something happened.)

When we initiate a turn we get an immediate increase in L, the lateral load, and the stiffer the shocks the faster and earlier that load transfer… hopefully while some of that negative camber still exists, because that’s when tires are most capable. If we don’t have much damping force from the shocks then the full lateral load may not hit until the car is fully rolled, at which time we are left only with the final camber state, which in Street class cars can often be positive instead of negative. (Tires don’t like that.)

But when people talk about weight transfer across the axle, they are probably thinking about something different. They are thinking about an increase in W.

When the body rolls, “weight” is transferred from one side of the car to the other, right? Well, that’s a vague way of talking about it. Yes, if you could put a scale under the tires while cornering it would say that “weight” has shifted, but really it is vertical load W that has increased, due to body roll, on one side of the car at the expense of the other side. That load increase is directly related to how much additional spring compression has occurred on one side, balanced by extension on the other side.

It’s also very possible that if the shocks are too stiff at the shaft speeds produced by turn-in they can shock the tire patches too much, too early and cause one end of the car to give up grip during the turn-in motion. However, this effect is somewhat in the driver’s control because she determines how fast she turns the steering wheel. All production car shocks and springs as delivered that I’ve ever slalomed are so soft that the driver can turn the wheel as fast as humanly possible and not create an immediate problem before you must turn back the other direction. At least on a dry surface. Sure, if you turn the wheel fast enough and far enough you can induce understeer in just about any production car. They are designed to do that. On purpose.

In any case, these dynamic effects are complicated and not well-understood by most casual autocrossers, automotive journalists and even some racing mechanics and engineers. Many books and articles about tuning car handling with shock changes are incomplete in their explanations and over-simplify the situation, offering various rules of thumb for tuning the balance with shocks. W in the diagram does increase faster with soft shocks because the car rolls faster. This is almost always a bad thing. So, look at the diagram again. An increase in W does not cause the car to turn. In fact, while increasing the lateral load capability of that tire, it decreases peak capability for turning because the inside tire is now lacking in vertical load and the sum of the two capabilities is less than if no weight transfer occurred. (We prefer to minimize weight transfer across the axle if at all possible. Usually the best way to do this is to lower the center of gravity while increasing the track width. Notice how wide and low most supercars have gotten in recent years? Much wider than necessary to hold two occupants comfortably, side by side.) An increase in L is what causes a car to turn and a fast increase in L allows a car to change direction quickly, with or without a significant increase in W.

If you take anything away from this post it should be this: the speed of lateral load transfer to the tires is a different effect from the speed of “weight” transfer to the tires caused by body roll and only one causes a car to turn. Both are highly influenced by shock absorber performance.