Frequently when we see great performers doing what they do, it strikes us that they’ve practiced for so long, and done it so many times, they can just do it automatically, But in fact, what they have achieved is the ability to avoid doing it automatically.

When we learn to do anything new-how to drive, for example-we go through three stages. The first stage demands a lot of attention as we try out the controls, learn the rules of driving, and so on. In the second stage we begin to coordinate our knowledge, linking movements together and more fluidly combining our actions with our knowledge of the car, the situation, and the rules. In the third stage we drive the car with barely a thought. It’s automatic. And with that our improvement at driving slowed dramatically, eventually stopping completely.

By contrast, great performers never allow themselves to reach the automatic, arrested-development stage in their chosen field. That is the effect of continual deliberate practice-avoiding automaticity. The essence of [deliberate] practice which is constantly trying to do the things one cannot do comfortably, makes automatic behavior impossible.

From Talent Is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else, by Geoff Colvin, 2008

Stage 1: Training the mind to learn the course prior to the first run

When we learn to autocross we go through stages. Unfortunately, there is not yet a firm consensus of what those stages are and how to best train for the transition through them. However, I have certain opinions on the subject.

This will not be a surprise to anyone who knows me!

I think three stages can be usefully identified and trained in order. I’m not sure how many posts it will take to get through them, but we might as well get started.

One caveat: The stages that we use to break down the learning of any skill are never absolute. They are a creation intended to support the design of a particular method of training. Hopefully it is a training method that was developed by someone with experience and skill. Since the training method is by nature designed not all designs will be equally effective, though any two different designs may be equally effective as long as they’re each followed faithfully.

In the art of Taiji that I practice there are commonly thought to be three basic stages. I heard a teacher remark that, while we are actually learning bits of all three stages almost from the beginning, it is important to focus on each stage in order. He referred with sadness to certain schools that basically skip the first stage and begin and concentrate on stage two, either by choice or ignorance. It’s not that one cannot make progress in stage two without stage one, but the progress is limited and the art is forever incomplete without mastering the stage one skills. I think autocross is similar, and one of the problems for beginners is that you tend to get all sorts of advice from well-meaning people, but the advice may come from what really should be different stages. This makes it difficult to figure out which advice to listen to and focus on.

One thing is for sure: we cannot be fast when the course is a series of constant surprises. Most beginners soon realize this, but may not know what to do about it. It takes them many tries at the course before it begins to click. In the beginning it may take more runs that you get in the day, so you never get to the point where you drive the course with confidence.

This is a problem unique to American autocross. The course is different at every event and we don’t get to practice it. We only get to walk it. Every run is timed and we only get a few runs. Only the fastest run counts.

I’ve heard (and read) many advanced drivers say “seat time is all you need.”

Seat time is needed, of course. But it’s not enough if you wish to get fast, fast.

Beginning with a club that offers at least six runs during a day (and hosts many events each season) is very advantageous because it may take that many runs to develop what a more advanced person would still call only a basic knowledge of the course. But, that sixth run may be the only one that’s really fun that day if it’s the only one where you aren’t worried about getting lost, even momentarily.

The mind can only do so much. If your focus is on recognizing the features within the course as you’re driving, then it can’t be on other things like surface composition, slight camber changes, grip changes, etc. So, we need a good way to quickly nail down our knowledge of the basic course layout so that we don’t have to focus on it as we drive. I call this learning the course.

Learning the course is a mental skill that requires development over time. The good news is that, as far as I can tell, anyone with normal mental capacity can become very good at it. The mental operation will become easy or at least easier. Like anything else it takes practice. But, what type of practice? Well, that’s why we do a course walk, right?

Do you think walking the course aimlessly is going to do the trick? Or, worse, walking the course distractedly? Or, even more depressing, how about walking the course with great focus, but focussed on the wrong things? None of these are likely to produce a good outcome anytime soon.

Now there are levels and levels for this sort of thing. The amount of detail that can be registered during course walks can vary tremendously from person to person. This is no different than expert-level achievement in any field. Experts always see more and remember more. You want to be an expert, right? OK, let’s go!

So, how do we get started training the mind to learn the course? We walk the course in a deliberate practice* sort of way. I recommend two disciplines. First, walk the course as many times as possible with mental focus. Your focus should be on imagining driving it at each point, at each step you take. Remind yourself to look ahead at each point in the course. Deliberately gaze way ahead and take in the view from each point. Decide where you should be looking at each location, both the direction and what items you will focus on, what cones you will wish to pick out and clearly see at speed and then do it.

Second, stop walking from time to time and draw the course, piece by piece, section by section, multiple times. You must have a pad and pencil with you as you walk. Break it down into sections. Once you have the sections, think about the transitions between sections. Don’t even try to connect it all together into one whole. It’s not necessary to be able to imagine driving the entire course in one continuous sequence. Save something for year five!

These two disciplines, walking with a particular focus and drawing the sections, are not necessarily “fun” in the normal sense of the word. They require mental work. You can’t be talking to your friends as you walk. (At least not the first few years.) You can’t be listening to someone else describe how they are going to drive the course. While that may be a very good thing to do from time to time, or on one of your multiple course walks, it will not help the training if you’re talking or listening on every course walk.

A caveat: Do not try to memorize the course. Walking the course with focus and drawing it is enough to make it seep into your subconscious. Not much will be surprising when you drive it. That’s all you need, because, we do not want to drive from memory. That would be too automatic as described in the quote from Talent Is Overrated, above. Every run is different. You must continually strive to drive faster each run, continually testing for the limits of traction, continuously improving your line. If you never feel the tires slide you’re not doing it right. Local conditions are always changing throughout the day. Your knowledge and feel for the course continually improves run to run. Your physical, emotional and mental states are constantly changing from moment to moment and, on some days, will affect your driving speed more than big changes in local conditions. Humans are not (yet) robots.

If you do these two things for 25 events, which is usually about one year for the moderately obsessed, you will probably be ready to focus on stage 2. But, don’t ever stop walking the course with focus and continue drawing the course for at least 50 events. Maybe that’s two years, maybe it’s five or even 10.

Examples

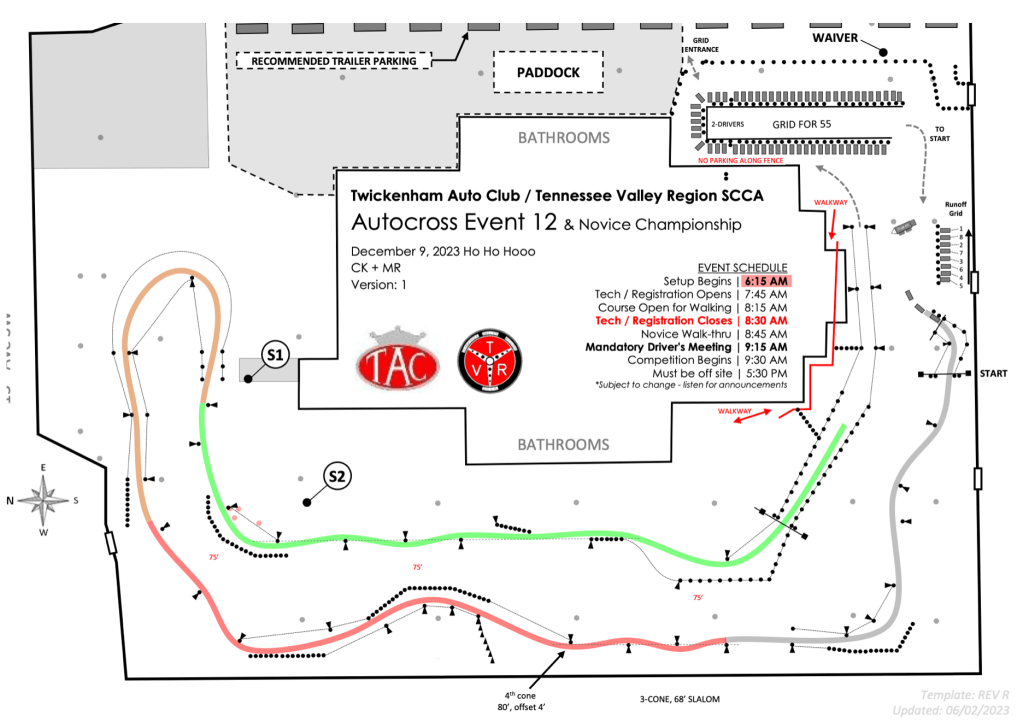

Below is the course map for our last local event in 2023. I’ll go through it as I would as a beginner, creating meaningful sections that I can remember and then string together. That’s step one. Then step two is to think about key transitions, or set-ups, between sections.

Section 1: Turning start into offsets

Section 2: 90-right into accelleration zone

Section 3: Slalom into the Hump

Section 4: Offsets into decreasing radius turnaround

Section 5: Fast 90-left into increasingly fast slalom

Section 6: Weird offset into a short finish

I suggest you read the names above and see if you can follow along on the map.

I reduced the whole course to six sections and six section names/descriptions. You don’t want too many… most people can remember about five to seven items, such as pieces on a chessboard. The funny thing is, the “items” can be single things or meaningful groups.

Non-chess experts, when shown a board with 20 to 25 pieces taken from actual games and then asked to recreate it, were found to be able to place only 4 or 5 pieces correctly. Chess Masters could generally recreate the entire board. They don’t remember 25 individual pieces, however. They remember five to seven recognizable groupings that have meaning within the game.

If the chess pieces were placed randomly, the chess experts could not remember any more than non-players. Similarly, if you try to memorize each turn in order within an autocross course… well, it’s basically hopeless.

When you first start autocross none of the course features mean anything to you, so remembering even five to seven groups will be difficult. You will, however, immediately begin to hear or read about named features, such as turnarounds, slaloms, offsets, decreasing and increasing radius corners, etc. You need to pick up on the lingo and ask people what the heck they’re talking about!

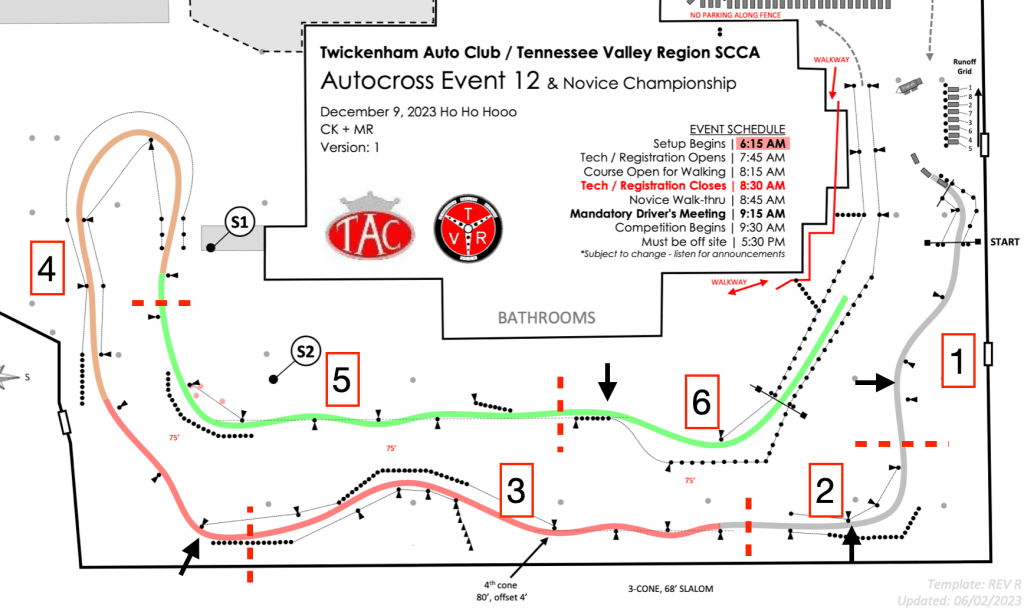

Here’s the map again, as I mentally separated it into 6 sections, numbered and with red-dashed dividing lines.

It doesn’t really matter how short or long each section is. What counts is that each one has a clear meaning to you as described by the words.

Part of the way I broke up the sections has to do with being able to see (when driving) all or most of the next section from the entry of that section. I think this is very helpful.

Another factor in how I broke the course into sections has to do with key setup points. For instance, between 1 and 2 I want to remember to stay tight left at the end of 1 (arrow) in order to be in a good position to enter 2.

I include the “acceleration zone” with the 90-right because it will remind me to add gas (arrow) as soon as possible coming out of the corner.

Similarly, at the end of 3 I need to remember to set up near the cone wall for the first turn cone of section 4 (arrow).

I include the decreasing radius turnaround as part of the section 4 description because what that means to me is that I must carry a lot of speed into the turnaround, only gradually slowing until the apex.

And then at the end of 5 the words “short finish” remind me that there is no setup for an acceleration into the finish because it comes up so soon. Therefore, I want to carry huge speed into section 6, brake and jerk the wheel hard right at the end of the last wall of cones (arrow) and continue to carry as much speed as possible around the last cone until I (hopefully) just barely miss the cone on the right side of the finish line. I anticipate that the car may be gradually slowing down the entire time in this section.

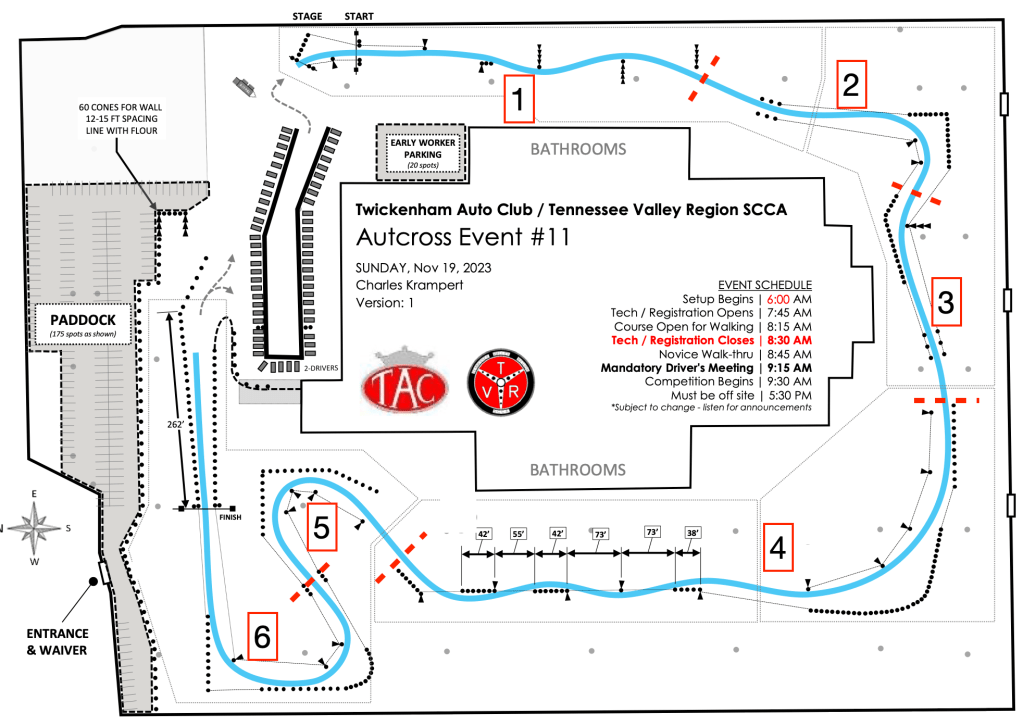

Here’s another example: the course map for the event previous to the one above. Please ignore the fact that “autocross” is misspelled!

Maybe you want to divide it up yourself? If so, go ahead and do it mentally before looking at how I did it.

Here are my sections descriptions.

Section 1: From Start, accelerate into a series of offsets

Section 2: Accelerate into a 90-right

Section 3: Turn left into a long acceleration zone

Section 4: Super-fast right sweeper into odd-spaced walloms

Section 5: 180 turnaround

Section 6: Two hard rights into the finish

…and the sections are illustrated below.

Once I have the sections in mind, I then decide about the setups in the transitions from one to the other. These are:

Between 1 and 2: get on the gas as early as possible after the last offset cone, but then brake early for the turn

Between 2 and 3: Exit the 90-right very tight in order to carry the most speed around 3’s left turn

Between 3 and 4: Carry speed like I’m insane knowing I can always lift to tighten the radius

Between 4 and 5: Backside the end cone of the first wall in the walloms

Between 5 and 6: Don’t fail to move the car left to set up for the first of two right turns

That’s basically how I mentally approached this course. This means I’m not driving one corner at a time. I’m driving one section at a time, with a key setup point within or at the end of each one.

The next installment for Stage 1 will cover the key driving skills that I think need to be understood, practiced and then developed within the first year of autocross. These will include developing a steering method, learning to shift some weight to the front before turning, trail-braking, coordinating steering and throttle after the apex, and learning to always be setting up.

*Deliberate Practice is a term first coined by psychologist K. Anders Ericsson to describe how people actually become experts in any field